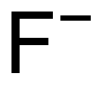

Fluoride ,

[3] [3] is an

inorganic,

monatomic anion of

fluorine with the

chemical formula F−. Fluoride is the simplest anion of fluorine. Its salts and minerals are important

chemical reagents and industrial chemicals, mainly used in the production of

hydrogen fluoride for

fluorocarbons. In terms of charge and size, the fluoride

ion resembles the

hydroxide ion. Fluoride ions occur on earth in several minerals, particularly

fluorite,

but are only present in trace quantities in water. Fluoride contributes

a distinctive bitter taste. It contributes no color to fluoride salts.

Nomenclature

The systematic name

fluoride, the valid

IUPAC name, is determined according to the additive nomenclature. However, the name

fluoride

is also used in compositional IUPAC nomenclature which does not take

the nature of bonding involved into account. Examples of such naming are

sulfur hexafluoride and

beryllium fluoride, which contain no fluoride ions whatsoever, although they do contain fluorine atoms.

Fluoride is also used non-systematically, to describe

compounds which releases hydrogen fluoride upon acidification, or a

compound that otherwise incorporates

fluorine in some form, such as

methyl fluoride and

fluorosilicic acid. Hydrogen fluoride is itself an example of a non-systematic name of this nature. However, it is also a

trivial name, and the

preferred IUPAC name for

fluorane.

Occurrence

Many fluoride minerals are known, but of paramount commercial importance is

fluorite (CaF

2), which is roughly 49% fluoride by mass.

[4] The soft, colorful mineral is found worldwide.

Seawater fluoride levels are usually in the range of 0.86 to 1.4 mg/L, and average 1.1 mg/L

[5] (milligrams per

litre or

ppm - parts per million

of fluorine by weight compared with water - effectively interchangeable terms). For comparison,

chloride concentration in seawater is about 19 g/L (19000 ppm). The low concentration of fluoride reflects the insolubility of the

alkaline earth fluorides, e.g., CaF

2.

Fluoride is present naturally in low concentration when drinking water and foods are based on

surface (rain/river) water... such water supplies generally contain between 0.01–0.3 ppm.

[6] Groundwater

(well water) concentrations vary even more, depending on the

composition of the local ground; for example under 0.05 ppm in parts of

Canada to 2800 mg/litre, although rarely exceeeds 10 mg/litre

[7]

- In some locations, the drinking water contains dangerously high levels of fluoride, leading to serious health problems.

- 50 million people receive water from water supplies that have close to the "optimal level".[8]

- In other locations the level of fluoride is very low, sometimes leading to fluoridation of public water supplies to bring the level to around 0.7-1.2 ppm.

Some plants concentrate fluoride from their environment more than

others. All tea leaves contain fluoride; however, mature leaves contain

as much as 10 to 20 times the fluoride levels of young leaves from the

same plant.

[9][10][11]

Chemical properties

Basicity

Fluoride can act as a

base. It can combine with a

proton (

H+):

- F− + H+ → HF

This neutralization reaction forms

hydrogen fluoride (HF), the conjugate acid of fluoride.

In aqueous solution, fluoride has a

pKb value of 10.8. It is therefore a

weak base,

and tends to remain as the fluoride ion rather than generating a

substantial amount of hydrogen fluoride. That is, the following

equilibrium favours the left-hand side in water:

- F− + H2O

HF + HO−

HF + HO−

However, upon prolonged contact with moisture, soluble fluoride salts

will decompose to their respective hydroxides or oxides, as the

hydrogen fluoride escapes. Fluoride is distinct in this regard among the

halides. The identity of the solvent can have a dramatic effect on the

equilibrium shifting it to the right-hand side, greatly increasing the

rate of decomposition.

Structure of fluoride salts

Salts

containing fluoride are numerous and adopt myriad structures. Typically

the fluoride anion is surrounded by four or six cations, as is typical

for other halides.

Sodium fluoride and

sodium chloride

adopt the same structure. For compounds containing more than one

fluoride per cation, the structures often deviate from those of the

chlorides, as illustrated by the main fluoride mineral

fluorite (CaF

2) where the Ca

2+ ions are surrounded by eight F

− centers. In CaCl

2, each Ca

2+ ion is surrounded by six Cl

− centers.

Inorganic chemistry

Upon treatment with a standard acid, fluoride salts convert to

hydrogen fluoride and metal

salts. With strong acids, it can be doubly protonated to give

H

2F+. Oxidation of fluoride gives fluorine. Solutions of inorganic fluorides in water contain F

− and

bifluoride HF−

2.

[12]

Few inorganic fluorides are soluble in water without undergoing

significant hydrolysis. In terms of its reactivity, fluoride differs

significantly from

chloride and other halides, and is more strongly solvated in

protic solvents due to its smaller radius/charge ratio. Its closest chemical relative is

hydroxide.

[citation needed] When relatively

unsolvated, for example in nonprotic solvents, fluoride anions are called "naked". Naked fluoride is a very strong

Lewis base,

[13] it is easily reacted with Lewis acids, forming strong adducts. Fluoride is susceptible to

extreme ultraviolet radiation, ejecting an electron to become highly reactive atomic fluorine. It has a

standard electrode potential of 2.87 volts.

[citation needed]

Biochemistry

At physiological pHs,

hydrogen fluoride is usually fully ionised to fluoride. In

biochemistry, fluoride and hydrogen fluoride are equivalent. Fluorine, in the form of fluoride, is considered to be a

micronutrient for human health, necessary to prevent dental cavities, and to promote healthy bone growth.

[14] The tea plant (

Camellia sinensis

L.) is a known accumulator of fluorine compounds, released upon forming

infusions such as the common beverage. The fluorine compounds decompose

into products including fluoride ions. Fluoride is the most

bioavailable form of fluorine, and as such, tea is potentially a vehicle

for fluoride dosing.

[15]

Approximately, fifty percent of absorbed fluoride is excreted renally

with a twenty-four-hour period. The remainder can be retained in the

oral cavity, and lower digestive tract. Fasting dramatically increases

the rate of fluoride absorption to near hundred percent, from a sixty to

eighty percent when taken with food.

[15]

Per a 2013 study, it was found that consumption of one litre of tea a

day, can potentially supply the daily recommended intake of 4 mg per

day. Some lower quality brands can supply up to a 120 percent of this

amount. Fasting can increase this to 150 percent. The study indicates

that tea drinking communities are at an increased risk of

dental and

skeletal fluorosis, in the case where water fluoridation is in effect.

[15] Fluoride ion in low doses in the mouth reduces tooth decay.

[16]

For this reason, it is used in toothpaste and water fluoridation. At

much higher doses and frequent exposure, fluoride causes health

complications and can be toxic.

Applications

Fluoride salts and hydrofluoric acid are the main fluorides of

industrial value. Compounds with C-F bonds fall into the realm of

organofluorine chemistry. The main uses of fluoride, in terms of volume, are in the production of cryolite, Na

3AlF

6. It is used in

aluminium smelting.

Formerly, it was mined, but now it is derived from hydrogen fluoride.

Fluorite is used on a large scale to separate slag in steel-making.

Mined

fluorite (CaF

2) is a commodity chemical used in steel-making.

Hydrofluoric acid and its anhydrous form,

hydrogen fluoride, is also used in the production of

fluorocarbons. Hydrofluoric acid has a variety of specialized applications, including its ability to dissolve glass.

[4]

Cavity prevention

Fluoride is sold in tablets for cavity prevention.

Fluoride-containing compounds, such as

sodium fluoride or

sodium monofluorophosphate are used in topical and systemic

fluoride therapy for preventing

tooth decay. They are used for

water fluoridation and in many products associated with

oral hygiene.

[17] Originally, sodium fluoride was used to fluoridate water;

hexafluorosilicic acid (H

2SiF

6) and its salt sodium hexafluorosilicate (Na

2SiF

6) are more commonly used additives, especially in the United States. The fluoridation of water is known to prevent tooth decay

[18][19] and is considered by the U.S.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as "one of 10 great public health achievements of the 20th century".

[20][21]

In some countries where large, centralized water systems are uncommon,

fluoride is delivered to the populace by fluoridating table salt. For

the method of action for cavity prevention, see

Fluoride therapy. Fluoridation of water has its critics (see

Water fluoridation controversy).

[22]

Biochemical reagent

Fluoride salts are commonly used in biological assay processing to

inhibit the activity of

phosphatases, such as

serine/

threonine phosphatases.

[23] Fluoride mimics the

nucleophilic hydroxide ion in these enzymes' active sites.

[24] Beryllium fluoride and

aluminium fluoride are also used as phosphatase inhibitors, since these compounds are structural mimics of the

phosphate group and can act as analogues of the

transition state of the reaction.

[25][26]

Estimated daily intake

Daily

intakes of fluoride can vary significantly according to the various

sources of exposure. Values ranging from 0.46 to 3.6–5.4 mg/day have

been reported in several studies (IPCS, 1984).

[14] In areas where water is

fluoridated

this can be expected to be a significant source of fluoride, however

fluoride is also naturally present in huge range of foods, in a wide

range of concentrations.

[27] The maximum safe daily consumption of fluoride is 10 mg for an adult.

Examples of fluoride content

| Food/Drink |

Fluoride

(mg per 100 g) |

Portion |

Fluoride

(mg per portion) |

| Black tea (brewed) |

0.373 |

1 cup, 240 g (8 fl oz) |

0.884 |

| Raisins, seedless |

0.234 |

small box, 43 g (1.5 oz) |

0.033 |

| Table wine |

0.153 |

Bottle, 750 ml (26.4 fl oz) |

1.150 |

Municipal tap-water,

(Fluoridated) |

0.081 |

Recommended daily intake,

3 litres (0.79 US gal) |

2.433 |

| Baked potatoes, Russet |

0.045 |

Medium potato, 140 g (0.3 lb) |

0.078 |

| Lamb |

0.032 |

Chop, 170 g (6 oz) |

0.054 |

| Carrots |

0.003 |

1 large carrot, 72 g (2.5 oz) |

0.002 |

Data taken from United States Department of Agriculture, National Nutrient Database

Safety

Ingestion

According

to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the Dietary Reference Intakes,

which is the "highest level of daily nutrient intake that is likely to

pose no risk of adverse health effects" specify 10 mg/day for most

people, corresponding to 10 L of fluoridated water with no risk. For

infants and young children the values are smaller, ranging from 0.7 mg/d

for infants to 2.2 mg/d.

[28] Water and food sources of fluoride include community water fluoridation, seafood, tea, and gelatin.

[29]

Soluble fluoride salts, of which

sodium fluoride is the most common, are toxic, and have resulted in both accidental and self-inflicted deaths from

acute poisoning.

[4]

The lethal dose for most adult humans is estimated at 5 to 10 g (which

is equivalent to 32 to 64 mg/kg elemental fluoride/kg body weight).

[30][31][32] A case of a fatal poisoning of an adult with 4 grams of sodium fluoride is documented,

[33] and a dose of 120 g sodium fluoride has been survived.

[34] For

sodium fluorosilicate (Na

2SiF

6), the

median lethal dose (LD

50) orally in rats is 0.125 g/kg, corresponding to 12.5 g for a 100 kg adult.

[35]

The fatal period ranges from 5 min to 12 hours.

[33] The mechanism of toxicity involves the combination of the fluoride anion with the calcium ions in the blood to form insoluble

calcium fluoride, resulting in

hypocalcemia; calcium is indispensable for the function of the nervous system, and the condition can be fatal.

Treatment may involve oral administration of dilute

calcium hydroxide or

calcium chloride to prevent further absorption, and injection of

calcium gluconate to increase the calcium levels in the blood.

[33] Hydrogen fluoride

is more dangerous than salts such as NaF because it is corrosive and

volatile, and can result in fatal exposure through inhalation or upon

contact with the skin; calcium gluconate gel is the usual antidote.

[36]

In the higher doses used to treat

osteoporosis,

sodium fluoride can cause pain in the legs and incomplete stress

fractures when the doses are too high; it also irritates the stomach,

sometimes so severely as to cause ulcers. Slow-release and

enteric-coated

versions of sodium fluoride do not have gastric side effects in any

significant way, and have milder and less frequent complications in the

bones.

[37] In the lower doses used for

water fluoridation, the only clear adverse effect is

dental fluorosis, which can alter the appearance of children's teeth during

tooth development; this is mostly mild and is unlikely to represent any real effect on aesthetic appearance or on public health.

[38]

Fluoride was known to enhance the measurement of bone mineral density

at the lumbar spine, but it was not effective for vertebral fractures

and provoked more non vertebral fractures.

[39]

A popular urban myth claims that the

Nazis used fluoride in concentration camps, but there is no historical evidence to prove this claim.

[40]

In areas that have naturally occurring high levels of fluoride in

groundwater which is used for

drinking water, both

dental and

skeletal fluorosis can be prevalent and severe.

[41]

Hazard maps for fluoride in groundwater

Around

one-third of the world’s population drinks water from groundwater

resources. Of this, about 10 percent, approximately 300 million people,

obtains water from groundwater resources that are heavily polluted with

arsenic or fluoride.

[42] These trace elements derive mainly from minerals.

[43] Maps are available of locations of potential problematic wells.

[44]

Topical

Concentrated fluoride solutions are corrosive.

[45] Gloves made of

nitrile

rubber are worn when handling fluoride compounds. The hazards of

solutions of fluoride salts depend on the concentration. In the presence

of

strong acids, fluoride salts release

hydrogen fluoride, which is corrosive, especially toward glass.

[4]

Other derivatives

Organic and inorganic anions are produced from fluoride, including:

See also

References

"Fluorides – PubChem Public Chemical Database". The PubChem Project. USA: National Center for Biotechnology Information. Identification.

"Fluorine anion". NIST. Retrieved July 4, 2012.

Wells, J.C. (2008). Longman pronunciation dictionary (3rd ed.). Harlow, England: Pearson Education Limited/Longman. p. 313. ISBN 9781405881180.. According to this source, is a possible pronunciation in British English.

Aigueperse,

Jean; Mollard, Paul; Devilliers, Didier; Chemla, Marius; Faron, Robert;

Romano, René; Cuer, Jean Pierre (2000). "Ullmann's Encyclopedia of

Industrial Chemistry". doi:10.1002/14356007.a11_307. ISBN 3527306730.

"Ambient Water Quality Criteria for Fluoride". Government of British Columbia. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

Liteplo, Dr R.; Gomes, R.; Howe, P.; Malcolm, Heath (2002). "FLUORIDES - Environmental Health Criteria 227 : 1st draft". Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 9241572272.

Fawell, J.K.; et al. "Fluoride in Drinking-water Background document for development of WHO Guidelines for Drinking-water Quality" (PDF). World Heath Organisation. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

Tiemann, Mary (April 5, 2013). "Fluoride in Drinking Water: A Review of Fluoridation and Regulation Issues" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. p. 3. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

Wong

MH, Fung KF, Carr HP (2003). "Aluminium and fluoride contents of tea,

with emphasis on brick tea and their health implications". Toxicology Letters. 137 (1–2): 111–20. doi:10.1016/S0378-4274(02)00385-5. PMID 12505437.

Malinowska

E, Inkielewicz I, Czarnowski W, Szefer P (2008). "Assessment of

fluoride concentration and daily intake by human from tea and herbal

infusions". Food Chem. Toxicol. 46 (3): 1055–61. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2007.10.039. PMID 18078704.

Gardner EJ, Ruxton CH, Leeds AR (2007). "Black tea--helpful or harmful? A review of the evidence". European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 61 (1): 3–18. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602489. PMID 16855537.

Wiberg; Holleman, A.F. (2001). Inorganic chemistry (1st English ed., [edited] by Nils Wiberg. ed.). San Diego, Calif. : Berlin: Academic Press, W. de Gruyter. ISBN 0-12-352651-5.[page needed]

Schwesinger,

Reinhard; Link, Reinhard; Wenzl, Peter; Kossek, Sebastian (2005).

"Anhydrous Phosphazenium Fluorides as Sources for Extremely Reactive

Fluoride Ions in Solution". Chemistry. 12 (2): 438–45. doi:10.1002/chem.200500838. PMID 16196062.

Fawell, J. "Fluoride in Drinking-water" (PDF). World Heath Organisation. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

Chan, Laura; Mehra, Aradhana; Saikat, Sohel; Lynch, Paul (May 2013). "Human exposure assessment of fluoride from tea (Camellia sinensis L.): A UK based issue?". Food Research International. 51 (2): 564–570. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2013.01.025. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

http://oradyne.net/fluoride-free-toothpaste/

McDonagh

M. S.; Whiting P. F.; Wilson P. M.; Sutton A. J.; Chestnutt I.; Cooper

J.; Misso K.; Bradley M.; Treasure E.; Kleijnen J. (2000). "Systematic review of water fluoridation". British Medical Journal. 321 (7265): 855–859. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7265.855. PMC 27492 . PMID 11021861.

. PMID 11021861.

Griffin SO, Regnier E, Griffin PM, Huntley V (2007). "Effectiveness of fluoride in preventing caries in adults". J. Dent. Res. 86 (5): 410–5. doi:10.1177/154405910708600504. PMID 17452559.

Winston A. E.; Bhaskar S. N. (1 November 1998). "Caries prevention in the 21st century". J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 129 (11): 1579–87. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.1998.0104. PMID 9818575.

"Community Water Fluoridation". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

"Ten Great Public Health Achievements in the 20th Century". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

Newbrun E (1996). "The fluoridation war: a scientific dispute or a religious argument?". J. Public Health Dent. 56 (5 Spec No): 246–52. doi:10.1111/j.1752-7325.1996.tb02447.x. PMID 9034969.

Nakai C, Thomas JA (1974). "Properties of a phosphoprotein phosphatase from bovine heart with activity on glycogen synthase, phosphorylase, and histone". J. Biol. Chem. 249 (20): 6459–67. PMID 4370977.

Schenk G, Elliott TW, Leung E, et al. (2008). "Crystal structures of a purple acid phosphatase, representing different steps of this enzyme's catalytic cycle". BMC Struct. Biol. 8: 6. doi:10.1186/1472-6807-8-6. PMC 2267794 . PMID 18234116.

. PMID 18234116.

Wang

W, Cho HS, Kim R, et al. (2002). "Structural characterization of the

reaction pathway in phosphoserine phosphatase: crystallographic

"snapshots" of intermediate states". J. Mol. Biol. 319 (2): 421–31. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00324-8. PMID 12051918.

Cho H, Wang W, Kim R, et al. (2001). "BeF(3)(-)

acts as a phosphate analog in proteins phosphorylated on aspartate:

structure of a BeF(3)(-) complex with phosphoserine phosphatase". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 (15): 8525–30. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98.8525C. doi:10.1073/pnas.131213698. PMC 37469 . PMID 11438683.

. PMID 11438683.

"Nutrient Lists". Agricultural Research Service United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 25 May 2014.

"Dietary Reference Intake Tables". United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

"Fluoride in diet". U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

Gosselin, RE; Smith RP; Hodge HC (1984). Clinical toxicology of commercial products. Baltimore (MD): Williams & Wilkins. pp. III–185–93. ISBN 0-683-03632-7.

Baselt, RC (2008). Disposition of toxic drugs and chemicals in man. Foster City (CA): Biomedical Publications. pp. 636–40. ISBN 978-0-9626523-7-0.

IPCS (2002). Environmental health criteria 227 (Fluoride). Geneva: International Programme on Chemical Safety, World Health Organization. p. 100. ISBN 92-4-157227-2.

Rabinowitch, IM (1945). "Acute Fluoride Poisoning". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 52 (4): 345–9. PMC 1581810 . PMID 20323400.

. PMID 20323400.

Abukurah AR, Moser AM Jr, Baird CL, Randall RE Jr, Setter JG, Blanke RV (1972). "Acute sodium fluoride poisoning". JAMA. 222 (7): 816–7. doi:10.1001/jama.1972.03210070046014. PMID 4677934.

The Merck Index, 12th edition, Merck & Co., Inc., 1996

Muriale

L, Lee E, Genovese J, Trend S (1996). "Fatality due to acute fluoride

poisoning following dermal contact with hydrofluoric acid in a

palynology laboratory". Ann. Occup. Hyg. 40 (6): 705–710. doi:10.1016/S0003-4878(96)00010-5. PMID 8958774.

Murray TM, Ste-Marie LG (1996). "Prevention

and management of osteoporosis: consensus statements from the

Scientific Advisory Board of the Osteoporosis Society of Canada. 7.

Fluoride therapy for osteoporosis". CMAJ. 155 (7): 949–54. PMC 1335460 . PMID 8837545.

. PMID 8837545.

National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) (2007). A systematic review of the efficacy and safety of fluoridation (PDF). ISBN 1-86496-415-4. Summary: Yeung CA (2008). "A systematic review of the efficacy and safety of fluoridation". Evid. Based Dent. 9 (2): 39–43. doi:10.1038/sj.ebd.6400578. PMID 18584000. Lay summary (PDF) – NHMRC (2007).

Haguenauer,

D; Welch, V; Shea, B; Tugwell, P; Adachi, JD; Wells, G (2000).

"Fluoride for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporotic fractures: a

meta-analysis.". Osteoporosis International. 11 (9): 727–38. doi:10.1007/s001980070051. PMID 11148800.

Bowers, Becky (6 October 2011). "Truth about fluoride doesn't include Nazi myth". PolitiFact.com. Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

World Health Organization (2004). "Fluoride in drinking-water" (PDF).

Eawag

(2015) Geogenic Contamination Handbook – Addressing Arsenic and

Fluoride in Drinking Water. C.A. Johnson, A. Bretzler (Eds.), Swiss

Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology (Eawag), Duebendorf,

Switzerland. (download:

www.eawag.ch/en/research/humanwelfare/drinkingwater/wrq/geogenic-contamination-handbook/)

Rodríguez-Lado,

L.; Sun, G.; Berg, M.; Zhang, Q.; Xue, H.; Zheng, Q.; Johnson, C.A.

(2013) Groundwater arsenic contamination throughout China. Science,

341(6148), 866-868, doi:10.1126/science.1237484

Groundwater Assessment Platform

Nakagawa M, Matsuya S, Shiraishi T, Ohta M (1999). "Effect of fluoride concentration and pH on corrosion behavior of titanium for dental use". Journal of Dental Research. 78 (9): 1568–72. doi:10.1177/00220345990780091201. PMID 10512392.

External links

|

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fluorides. |